CASE SUMMARY

- A 68-year-old woman presented to her physician with symptoms of mild fatigue, moderate night sweats, and abdominal pain/fullness lasting 4 months; she also reported increased bruising and an unexplained 12-lb weight loss.

- Her spleen was palpable 8 cm below the left costal margin.

- Karyotype: 46XX

- Bone marrow biopsy results: megakaryocyte proliferation and atypia with evidence of reticulin fibrosis

- Genetic testing results: JAK2 V617F mutation; CALR negative

- A blood smear revealed leukoerythroblastosis.

- Laboratory values:

- Red blood cell count: 3.40 × 1012/L

- Hemoglobin level: 13.2 g/dL

- Hematocrit: 36%

- Mean corpuscular volume: 94 fL

- White blood cell count: 23.0 × 109/L

- Platelet count: 450 × 109/L

- Peripheral blood blasts: 1%

- Diagnosis: primary myelofibrosis

- Risk:

- International Prognostic Scoring System: intermediate-2

- Mutation and Karyotype-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System for Primary Myelofibrosis in adults 70 and younger: intermediate

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: How do the 3 Janus kinase ( JAK) inhibitors that are approved in this setting compare with each other?

HOBBS: Ruxolitinib [Jakafi] was the first JAK inhibitor [to be approved].1 I think they got lucky that it got approved way before fedratinib [Inrebic]2 and pacritinib [Vonjo],3 even though I think it’s worth noting [that] fedratinib and pacritinib… started their process of clinical trials a long time ago. Unfortunately, they ended up getting held up during their trials.

The indications of these 3 drugs are fairly similar: intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis (for pacritinib, specifically for patients with platelet counts of less than 50 × 109/L).4-6 For ruxolitinib, the [starting dose] is based on platelet count, not on hemoglobin level.4

In practice, probably a lot of physicians don’t adhere strictly to the platelet criteria, and in a patient who is a little frail or cytopenic or who has anemia, you could maybe start at a lower dose and then escalate, depending on how they tolerate the treatment. Fedratinib is given as a [once-daily] dose of 400 mg, and it was studied in patients with a platelet count of at least 50 × 109/L.5 The dose of pacritinib is 200 mg twice daily.6 So ruxolitinib is the only one where you really [adjust] the dose a lot.

CASE UPDATE

The patient is not interested in transplant; a decision was made to initiate ruxolitinib.

What clinical trial data supported the use of ruxolitinib?

It’s amazing that these data are 11 years old. The studies were published in The New England Journal of Medicine. These data came from phase 3 randomized studies that compared ruxolitinib with placebo in COMFORT-I [NCT00952289] and ruxolitinib with best available therapy in COMFORT-II [NCT00934544].

The COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II studies demonstrated very similar things, [with ruxolitinib leading] to a significantly improved decrease in spleen volume [the percentage of patients with at least a 35% reduction; reductions of 41.9% and 28% were seen in the experimental arms of COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II, respectively]. Most patients on ruxolitinib had some improvement in splenomegaly, even if they didn’t meet the arbitrary 35% spleen volume reduction [cutoff].7,8

Similarly, patients on ruxolitinib compared with both placebo and best available therapy had a significant improvement in symptoms.7,8 In my experience, for patients who have lots of symptoms like itching and so on, there’s really nothing that can make those symptoms go away [as well as] the JAK inhibitors do.

The COMFORT studies used the Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Symptom Assessment Form plus other measures. These studies demonstrated that there was an improvement in symptoms like fatigue and appetite issues, and there was also overall improvement in global health status and functional status.7,8

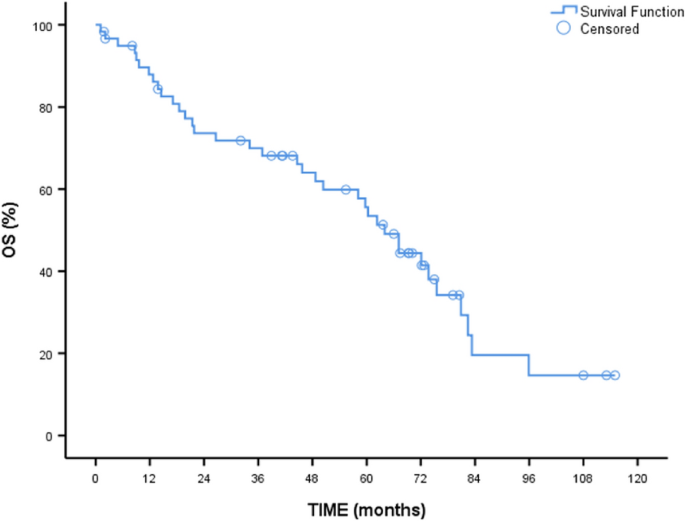

The long-term data from the COMFORT studies have shown a survival benefit in the patients who were treated with ruxolitinib [median overall survival (pooled data from both studies), 5.3 years vs 3.8 years for the experimental and control arms, respectively].7,9

I think it’s interesting to think about why that was. Was it because of less transformation to leukemia, or was it because of an improved functional status and the ability to eat, drink, and be more functional and have a decreased inflammatory state? I think that is still unclear.

What was the relationship between spleen response and survival among patients treated with ruxolitinib?

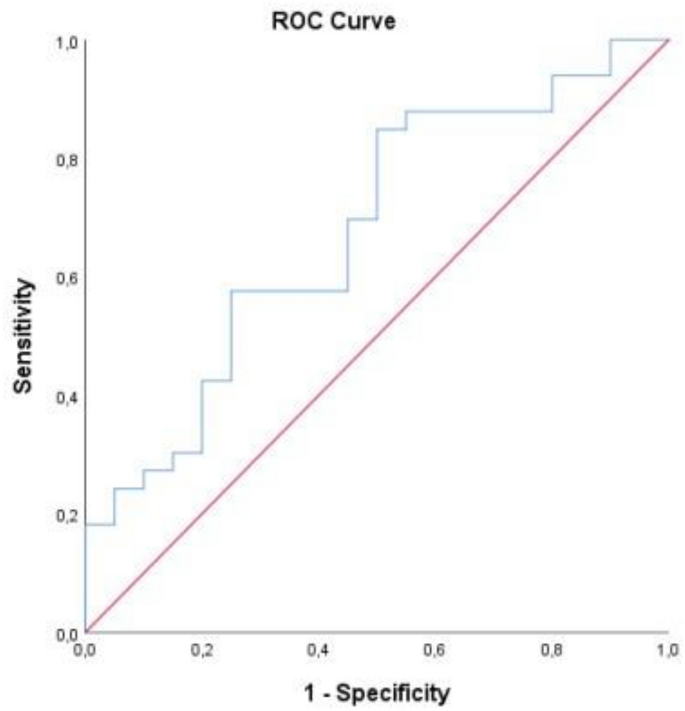

Even though we don’t know the mechanism that’s driving the survival benefit, we do know that spleen response did correlate with outcomes [in a multicenter study of ruxolitinib]. Patients who had a spleen response seemed to do better than those who didn’t.10 And I think that’s intuitive. Patients who have more resistant disease obviously aren’t going to do as well.

What was the relationship between ruxolitinib dose and response (spleen volume or total symptom score) in the COMFORT-I trial?

An important point is that if you give a low dose of a JAK inhibitor, it’s not going to be that effective. That was definitely true for the spleen. Ruxolitinib was more effective at higher doses for spleen volume reduction. Interestingly, for symptom improvement, some patients had a good response with respect to some of their symptoms with a lower dose, but to get the maximal spleen response, you needed a higher dose. The responses didn’t always track exactly together.11

How was ruxolitinib tolerated in these studies?

It was, in general, well tolerated. But not surprisingly, ruxolitinib was associated with higher rates of anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia compared with placebo [and best available therapy].7,8

What data inform the use of ruxolitinib in patients with a platelet count in the range of 50 × 109/L to 100 × 109/L?

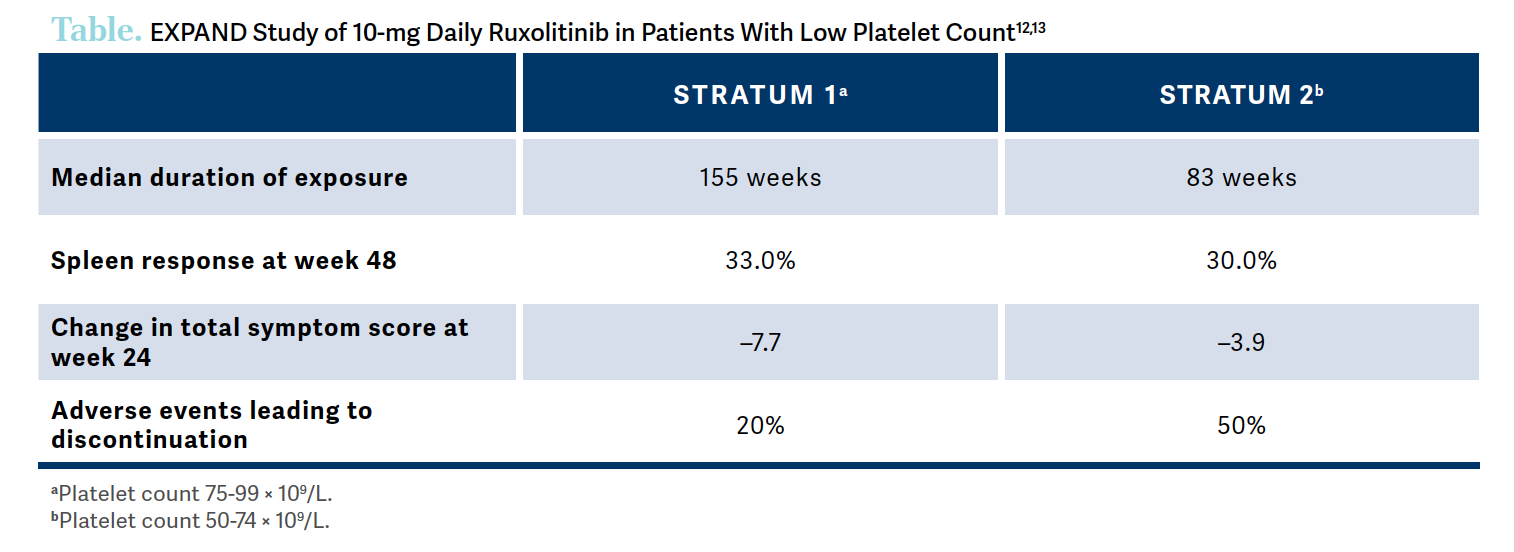

We know how to use ruxolitinib, [but] we use it on-label, [so when a patient’s platelet count is] below 100 × 109/L, we [don’t know] what to do. Do we give 5 mg? We know that a lower dose of ruxolitinib is not that effective. There was a study called EXPAND [NCT01317875], a phase 1b dose-finding study that evaluated different starting doses of ruxolitinib in patients with low platelet counts.

The patients were divided into a group of patients with platelet counts of 75 × 109/L to 99 × 109/L and another group of patients with platelet counts of 50 × 109/L to 74 × 109/L. They demonstrated that 10 mg twice daily was the maximal safe dose for both groups and showed that patients were able to stay on that dose.12,13

Similar to the COMFORT studies, the results of the EXPAND study showed that even if patients had low platelets, if they were treated with a slightly higher dose of ruxolitinib, they ended up having a pretty good response in terms of symptoms as well as in terms of spleen volume [Table].12,13 These data highlight that it’s probably safe to give ruxolitinib at lower platelet counts and also demonstrate that the higher dose, more than 5 mg, is associated with a greater improvement in spleen [volume reduction] in particular.

What data inform the use of ruxolitinib in patients with anemia of grade 3 or 4?

[Nearly half of the] patients on the COMFORT-I study had anemia at baseline.7,8 Importantly, efficacy was maintained despite anemia, and although some patients had to adjust their dose or receive a transfusion, [less than 1% of patients] had to discontinue ruxolitinib because of anemia.7 I would imagine that in the real world that would probably be different.

Some ruxolitinib studies have shown that if a patient develops anemia while on ruxolitinib, it’s not as bad as if they have anemia de novo, especially if that happens early in treatment.14 Of course, if a patient has been on ruxolitinib for a year or 2 and all of a sudden [develops] anemia, that’s different and probably related to disease progression.

It’s important to note that if you put a patient on ruxolitinib, they [can] become a little bit anemic. Some of them will [be anemic] the first month and then find their new baseline, which isn’t always exactly where they were before but is a little higher than the nadir. But that decrease at the beginning of treatment is not as concerning as that anemia that we see in patients who present up front with anemia.

How does a patient’s baseline hemoglobin level influence your decision of whether to give ruxolitinib?

I feel comfortable giving the drug. I would probably not give the on-label dose on the basis of their platelet count because especially those patients who are in the 7 [g/dL hemoglobin] range, I’m going to make them transfusion dependent.

But it’s something that warrants a conversation. It depends on how symptomatic that patient is. If a patient has horrible night sweats and is bothered by their spleen, they may not be as bothered by their anemia. But I do struggle with that, so if the patient is not that symptomatic, maybe I won’t push that JAK inhibitor as much or the dose as much.

It depends on the situation. Many times, I’ll do the JAK inhibitor alongside an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent [ESA] or something like that. I don’t love the recommendation to just give the [on-label] dose and give transfusions. I would prefer not to have to give transfusions.

Q:If the erythropoietin level is less than 500 mU/mL, do you give ruxolitinib? Do you add other agents?

I’ll try danazol or an ESA. Personally, I haven’t had that much success with ESAs in myelofibrosis. I’ve used luspatercept-aamt [Reblozyl] off-label, both with ruxolitinib and by itself, but…some of the insurances require that I try the ESA first.

Q:Would you consider using lenalidomide (Revlimid)?

I rarely end up using it. It is a little better tolerated than thalidomide [Thalomid]. It’s definitely an option, especially for those patients with thrombocytopenia [because] you don’t have much else to do. But I don’t find [these drugs] to be the most well tolerated. But that is definitely a recommendation. You can use [lenalidomide] to try to help with anemia.

REFERENCES

1. Deisseroth A, Kaminskas E, Grillo J, et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval: ruxolitinib for the treatment of patients with intermediate and high-risk myelofibrosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(12):3212-3217. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0653

2. FDA approves fedratinib for myelofibrosis. FDA. Updated August 16, 2019. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/5ej7s4tx

3. FDA approves drug for adults with rare form of bone marrow disorder. News release. FDA. March 1, 2022. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/4jcus8km

4. Jakafi. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2023. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/ua3rzhwr

5. Inrebic. Prescribing information. Bristol Myers Squibb; 2023. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/ms6emc6k

6. Vonjo. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/5bpdwhku

7. Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557

8. Harrison C, Kiladjian JJ, Al-Ali HK, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):787-798. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110556

9. Verstovsek S, Gotlib J, Mesa RA, et al. Long-term survival in patients treated with ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis: COMFORT-I and -II pooled analyses. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):156. doi:10.1186/s13045-017-0527-7

10. Palandri F, Palumbo GA, Bonifacio M, et al. Durability of spleen response affects the outcome of ruxolitinib-treated patients with myelofibrosis: results from a multicentre study on 284 patients. Leuk Res. 2018;74:86-88. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2018.10.001

11. Verstovsek S, Gotlib J, Gupta V, et al. Management of cytopenias in patients with myelofibrosis treated with ruxolitinib and effect of dose modifications on efficacy outcomes. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;7:13-21. doi:10.2147/OTT.S53348

12. Vannucchi AM, Te Boekhorst PAW, Harrison CN, et al. EXPAND, a dose-finding study of ruxolitinib in patients with myelofibrosis and low platelet counts: 48-week follow-up analysis. Haematologica. 2019;104(5):947-954. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.204602

13. Gugleilmelli P, Kiladijan JJ, Vannucchi A, et al. The final analysis of Expand: a phase 1b, open-label, dose-finding study of ruxolitinib (RUX) in patients (pts) with myelofibrosis (MF) and low platelet (PLT) count (50 × 109/L to < 100 × 109/L) at baseline. Poster presented at: 62nd American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition; December 5-8, 2020; virtual. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/bdzymsst

14. Gupta V, Harrison C, Hexner EO, et al. The impact of anemia on overall survival in patients with myelofibrosis treated with ruxolitinib in the COMFORT studies. Haematologica. 2016;101(12):e482-e484. doi:10.3324/haematol.2016.151449